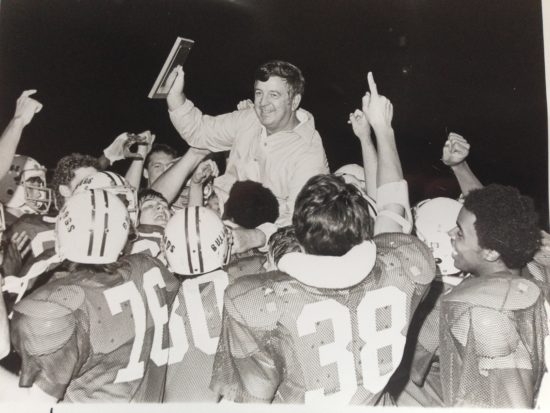

Building Bridges: Remembering HS football coach Ben Jones

A look at how Jones successfully united Mississippi’s first integrated high school football team

He wanted to make sure his players knew how he felt. So, the night of Itawamba Agricultural High School’s first game of the 1967 football season, coach Ben Jones had all his players walk around the field with their helmets off.

He wanted the crowd to see his team — which that night was the first in Mississippi to include black players — and for those athletes to know he stood with them.

That’s how Jones supported all his teams and players, until he died July 7.“Once he knew you as a young person, he followed you for life,” said Mike Mills, who played for Jones in 1972 and 1973. “If your parents died, he was at the funeral. If you were running for public office, he was at the rallies. He just was involved in everybody’s life in a very positive way.”

Football in Mississippi

Before 1967, African-Americans in Fulton, Mississippi, had no experience playing football. Segregated schools didn’t field teams, so in the buildup to the 1967 season, Jones was tasked with not only handling the integration of a football team, but also teaching a number of his players the basics of the game.

That didn’t affect how he ran his preseason camp. Roy Gregory played on Jones’ first team at Itawamba in 1963, when Jones won a conference title despite arriving at the school just two weeks before the season began.

“The thing about coach Jones is he was a great motivator and a great motivator of people,” Gregory said. “He had tremendous leadership qualities, and he knew how to touch different buttons.”

After Gregory graduated, he returned each summer to help Jones with preseason camps, including the 1967 season. He said there was nothing different about how Jones operated.

“There was never any problem,” Gregory said. “To my knowledge, there were never any racial problems around the football team through those years. He did a tremendous job of pulling everybody together.”

“It just wasn’t a problem for us,” Mills said. “The reason for that was because everyone had the same chance and same opportunity to participate. We were all good friends, and some of my friends for life came out of the African-American community.”

Everyone gets a chance

Jones made it clear early on that if a player was good enough, that player would be on the field. He instituted a “fairness rule,” a method that meant if a player thought he was better than a starter at that position, he could challenge for his spot. If he won, he started.

Jones made it clear early on that if a player was good enough, that player would be on the field. He instituted a “fairness rule,” a method that meant if a player thought he was better than a starter at that position, he could challenge for his spot. If he won, he started.

“He was going to play the best people and gave everybody an opportunity to excel,” Gregory said. “That first group, they were some good athletes. One or two of them played in the NFL, and some played in college.”

That included Roy Lee Crayton, one of the first black players on Jones’ team. He helped ease any tension in the first game of 1967 when he deflected a pass, leading to an interception that was returned for a touchdown. Itawamba won the game, 28-7.

Robert Clay, who played for Jones from 1968-70, said the fairness rule made it evident there would be no discrimination on Jones’ field.

“He just always made it clear there wasn’t going to be any picking and choosing,” Clay said. “He always said the best man would play. All of us black guys, who had never played football before, we all took advantage of that. We strived to be the best.”

In Clay’s sophomore season, he was seeing time as a linebacker, wide receiver and tight end, despite possessing no formal football experience.

“I talked with some of the guys ahead of me, and they told me he was not a prejudiced person,” Clay said. “He didn’t have a prejudiced bone in his body. He wanted you to strive for greatness, whatever color you were. He wanted you to be the best you could be.”

Clay was a standout his first two seasons, and at the end of his junior year Jones said he wanted try Clay at quarterback. There had never been a black quarterback in the Tombigbee Conference, so Clay gave it little thought.

Then, at the start of camp the following year, Jones put Clay under center. He started at quarterback the entire year and was named All-State. That helped earn him a scholarship to Mississippi Valley State, where he played defensive back.

“We didn’t expect to have much opportunity,” Clay said. “We had seen racial stuff just walking the street. After we integrated we expected to be treated like that, but after we integrated we never saw anything like that. He always made it so we were a part of the team.

“We never felt inferior to the white players. We felt like we were part of the team and that if we were the best, we would have a chance to play. A lot of people tried to discourage him from playing the black players, but that never discouraged him from playing the best. He took a lot of criticism in the neighborhood, but he didn’t care.”

Clay, and all of Jones’ players, said it genuinely felt like he was interested in them beyond what happened on the field.

That’s what Gregory felt as he rose through the coaching ranks, eventually leading the Austin Peay University football team from 1991-96. Gregory still remembers Jones sitting in the front row at his coaching clinics, vigorously taking notes along with fresh-faced coaches new to the game.

Jones continued helping Mills, who rose through the Mississippi legislature to become a district court judge. Without Jones, Mills isn’t sure he would have made it.

“You sensed that he was special,” Mills said. “We were from a county with a lot of poor kids — white and black — in northeast Mississippi. Whether we knew it or not, many of us needed a successful role models in our lives and he was that. He taught us how to live.”