Powerline: Returning to action after a layoff

There have been some unfortunate incidents involving collegiate student-athletes related to conditioning procedures. Several of these occurrences took place after the athletes returned from an extended break.

The return point from a long layoff is a sensitive period, and precautions must be in place to protect athletes engaged in conditioning activities. A crucial premise to adhere to is that post-layoff program construction must be planned with the understanding that most of the athletes have probably been fairly sedentary over the break. This holds true regardless of whether the athletes were sent home with an optional “vacation workout.”

The return point from a long layoff is a sensitive period, and precautions must be in place to protect athletes engaged in conditioning activities. A crucial premise to adhere to is that post-layoff program construction must be planned with the understanding that most of the athletes have probably been fairly sedentary over the break. This holds true regardless of whether the athletes were sent home with an optional “vacation workout.”

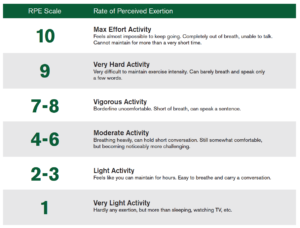

Upon return from a layoff, there may be alterations in plasma volume, and this can have several effects, including impaired thermoregulation and cardiovascular function, reduced stroke volume, increased rate of perceived exertion (RPE) at a given work load, and reduced respiratory/anaerobic threshold.

Increases in lactate occur at a lower percentage of maximal work. The reduced pH values associated with these occurrences can impact the limbic system, muscle function and muscle breakdown. In individuals with sickle-cell trait or impaired kidney function, these responses can be amplified. This is why identifying sickle-cell trait individuals is critical.

Conditioning considerations

A deconditioned athlete may have an anaerobic threshold of 50 to 60 percent max VO2. A well-conditioned athlete can be in the neighborhood of 80 to 90 percent max VO2. These two athletes on the same team have drastically different responses and perceptions with respect to the same workout.

Special consideration must be given to respite-time-to-work-time ratios during conditioning procedures, especially at the onset. A recommendation for relief: Work ratios over a 10-week span is as follows:

- Weeks one to three: Relief-to-work ratio is a minimum of 4:1.

- Weeks four to seven: Relief-to-work ratio is a minimum of 3:1.

- Weeks eight to 10: Relief-to-work ratio is a minimum of 2½:1.

Rate of perceived exertion (RPE) should be in effect during all phases. If athletes have noticeable difficulties handling the workload, volume or relief intervals, immediate adjustments should be made. This holds especially true when there is a sudden and drastic increase in heat and humidity over the norm.

Strength training considerations

Total training load in strength training is determined by multiplying reps, sets and weight load. Strength training workouts upon return should be no higher than 60 percent of the highest achieved training load prior to the layoff. RPE also should be incorporated into determining training load intensity in the return process. Athletes who have been training consistently during the layoff, and especially those who have not, can make adjustments under the strength coach’s direction to match RPE.

Those at the greatest risk are those with sickle-cell traits and athletes who are overweight, dehydrated or not adequately heat acclimated.

Exertional rhabdomyolysis (ER)

ER is a syndrome of diverse etiology, characterized by destruction of the skeletal cell membrane resulting in massive release of intercellular creatine kinase (CK), potassium, myoglobin and other intracellular constituents. ER can occur in response to strenuous physical activity, or particularly overzealous eccentric loading, where mechanical or metabolic stress damages muscle fibers.

This muscle damage can occur in the absence of high environmental temperatures, but ER also is seen as a consequence of exertional heat exposure, coexisting with sickle-cell trait or use of certain dietary supplements.

CK levels may peak between 12 and 96 hours after the end of exercise and then decline progressively. Musculoskeletal pain typically occurs 24 to 48 hours after extreme or non-familiar exercise. Cola-colored urine is the primary sign reported by persons experiencing acute ER.

Acute exertional rhabdomyolysis in athletes is most commonly caused by novel overexertion, or performing too much new physical work without adequate lead-in and progression. Many examples of novel overexertion exist in the medical literature regarding acute ER, and there are diverse predisposing factors: Athletes who are overweight, unfit, features of various illnesses, environmental features (heat stress), inborn metabolic myopathies, and certain drugs or supplements.

ER that is associated with sickle-cell trait is of great concern. Due to log-jamming of red cells in vessels supplying the working muscles, ischemic rhabdomyolysis ensues. This initiates major lactic acidosis and a rapid rise in serum potassium, which can cause lethal arrhythmias or death from acute myoglobinuric renal failure.

Strenuous exercise alone may not be the only factor in the cascade of events leading to ER in people with sickle-cell trait. Dehydration may contribute to the developing of sickling in muscle capillaries, and people with sickle-cell trait might be more naturally predisposed to dehydration due to their inability to concentrate their urine when deprived of water. This defect might make sickle-cell individuals less able to conserve water. Athletes with sickle-cell trait may require larger water intake to maintain proper fluid balance.

The primary risk factors for ER in persons with sickle-cell trait include:

- Extreme heat/humidity

- High altitude

- Exercise-induced asthma

- Pre-event fatigue due to illness or lack of sleep.

Hydration status

Athletes returning from a layoff to climates with higher heat/humidity may not be properly hydrated at the onset of training. Oftentimes, the first workouts upon return are early in the morning, when athletes are not at optimal hydration levels. Athletes must be encouraged to begin hydration strategies several days before returning to conditioning following a layoff. These strategies should be devised with input from the sports medicine staff and a registered dietician.

Supplements

So-called energy drinks and highly caffeinated pre-workout supplements can sometimes lead to physiological complications, which can be exacerbated when combined with the initiation of exercise after a layoff. Potential increases in blood pressure, tachycardia and peripheral vasoconstriction, which can lead to increases in core temperature, can occur. It’s also possible that the increase in “perceived energy” from some of these supplements may lead an athlete to overexertion.

All over-the-counter supplements used by your athletes should be cleared by a member of the sports medicine staff or a registered dietician.

The culture

All coaches want a culture where hard work is embraced. However, keep in mind that there is a thin line between a solid work ethic and a serious danger zone. That line must never be crossed.

New coaching staffs often want to identify slackers or individuals who do not embody the cultural characteristics presented by the head coach and their staff. However, using conditioning sessions to weed out less than desirable individuals is counter to the intent, purpose and healthy outcome goals of training. It also violates program integrity and every standard for keeping the safety of the athletes in forefront.

Rather than using conditioning as means for eliminating individuals, it must be kept in its appropriate context for gradual, progressive and safe training procedures, and as a trust-building endeavor from a psychological standpoint.

Ted Lambrinides, PhD, is director of sports science for Athletic Strength and Power, and Ken Mannie is the head strength/conditioning coach at Michigan State University. To contact him about this topic or anything else you’ve read in Powerline, send him an email at [email protected].

References

- Chavez L., Leon, M., Einav, S., Varon, J., Beyond Muscle Destruction: A Systematic Review of Rhabdomyolysis for Clinical Practice, Critical Care, 20:135, 2016.

- Eichner, E.R., Sickle Cell Trait, Journal of Sports Rehabilitation, 16:197-203, 2007.

- NATA Position Statement: Preventing Sudden Death in Sports, Journal of Athletic Training, Jan./Feb., 2012.

- Williams, J., Thorpe, C., Rhabdomyolysis, Continuing Education in Anesthesia, Critical Care, and Pain, 14:4, 2014.

Book Review

Principles of Athletic Strength and Conditioning: The Foundations of Success in Training and Developing the Complete Athlete, edited by Jim Kielbaso and Toby Brooks, Crew Press, 2017.

Sixteen leaders in the field of strength and conditioning, with a total of more than 300 years of collective coaching experience, combined their expertise and efforts to produce a definitive text on proper and productive training for athletes. Each author penned a chapter in this comprehensive manual that covers topics such as specific energy system training, testing and evaluation, flexibility and mobility techniques, program design, training the multisport athlete, the importance of head and neck training, considerations for the female athlete, increasing power, and speed improvement strategies. Psychological components are also covered masterfully in an excellent chapter on motivation and leadership through coaching.

Sixteen leaders in the field of strength and conditioning, with a total of more than 300 years of collective coaching experience, combined their expertise and efforts to produce a definitive text on proper and productive training for athletes. Each author penned a chapter in this comprehensive manual that covers topics such as specific energy system training, testing and evaluation, flexibility and mobility techniques, program design, training the multisport athlete, the importance of head and neck training, considerations for the female athlete, increasing power, and speed improvement strategies. Psychological components are also covered masterfully in an excellent chapter on motivation and leadership through coaching.

This manual is an artful marriage of science and practical application. Designed with the “coach in the trenches” in mind, the principles presented can be applied in several different settings, regardless of sport, available equipment or overall resources.

It’s a must-have for all coaches searching for state-of-the-art, evidence-based and easily incorporated training procedures.

Find the book at www.iyca.org or on Amazon.