Climate Control: Handling Heat Acclimation in Athletes

The entire sports world hopes and prays for a return to normalcy by the Autumn of 2020 following a spring and summer rife with cancellations and disappointments. A return to the former status quo would mean that fall athletes will be gearing up for their seasons, with practices beginning in the dog days of summer.

Dr. Douglas Casa, a professor of kinesiology and the director of athletic training education at the University of Connecticut, believes that teams are entering uncharted territory this fall in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic. Casa, also the chief executive officer at the Korey Stringer Institute, whose mission is educating about and preventing heat-related illnesses and issues among athletes, said that great care must be taken by everyone involved this coming summer to keep players safe.

“This is one of the most unique years in history, with the prolonged absence of sports and conditioning,” Casa said. “How are we going to phase people back? That’s a great concern.”Dr. Casa said that this coming summer will bring more challenges than ever for student-athletes and the coaching staff that guide them thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic and the quarantines that accompanied it. Dr. Casa said that coaches should be prepared to see that their athletes, for the most part, will not have the same level of fitness that they had in previous years entering the start of the fall sports season.

“So many football players use the spring — playing lacrosse, or baseball, or track and field — to stay in shape for football season and then continue to work out over the summer. This year they’ve lost those opportunities to play those sports in school, and have not been able to keep up with their usual regiments,” Casa said. “Coaching staff should be ready for that.”

Casa added that coaches should expect that a portion of their rosters will be up to speed, but that number, he expects, will be lower than previous seasons. The bottom of the roster, the players that do little to ready themselves for the season before practices begin, might be more profound than the normal year, he thought.

Those players are the ones most at risk for having heat-related health issues. According to studies done by the Stringer Institute, it has been determined that athletes that have lower levels of fitness are more likely to be affected. Additionally, they are the ones that typically have done the least amount of work to condition their bodies to deal with the higher summer temperatures.

Those players are the ones most at risk for having heat-related health issues. According to studies done by the Stringer Institute, it has been determined that athletes that have lower levels of fitness are more likely to be affected. Additionally, they are the ones that typically have done the least amount of work to condition their bodies to deal with the higher summer temperatures.

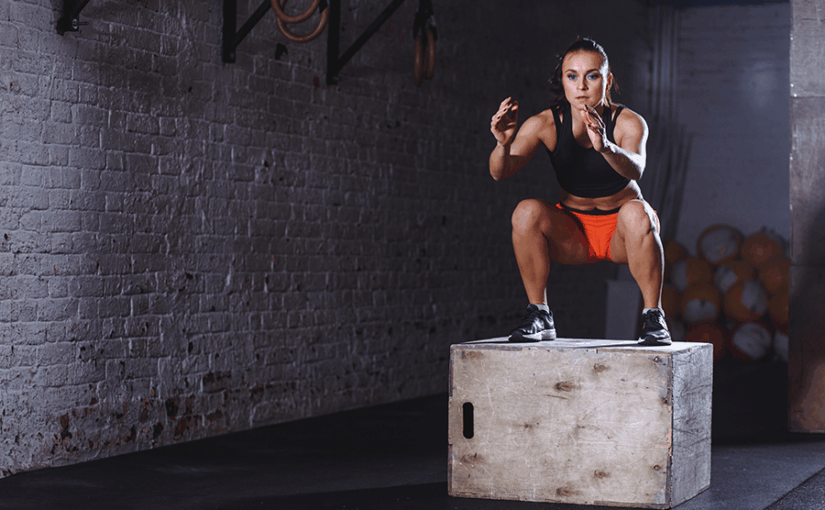

Dr. Casa said that heat acclimation by athletes is the best way for them to prepare themselves for the rigors of August and September practices and games.

“They need to be focusing on June and July,” he said. “When you’re first exposed to heat, you want to go in slowly…starting out with exercise during the cooler parts of the day and then working up to exercising during the hotter hours of the day.”

According to the doctor, football and cross country are the two sports that deal with the most heat-related illnesses and have seen the most deaths by athletes. He said that both coaches and athletes need to be cognizant of how acclimated the athletes are to the heat, and take measures to make sure that they do not put themselves into dangerous situations.

Trust in the Trainers

In North Carolina, athletes know a thing or two about the uncomfortable summer heat. The average temperature in the Tar Heel State is in the high 70s from July to September, with humidity to match. The sticky days and nights make training for the fall season a slog for all involved.

Deran Coe said that the boys and girls under his umbrella in the Wake County School District, based in Cary, North Carolina, know that they must be ready for an uncomfortable start to their fall season every year. Coe oversees 24 high schools and 39 middle schools at the Director of Athletics for the 15th largest public school district in the United States.

He said that communication is key for his school system in its efforts to prevent heat injuries, starting with the support system that is in place as a bridge between the athletes and the coaches.

“All of our high schools have certified athletic trainers,” explained Coe. “They are the ones that govern how the day is approached in regards to heat management.”

Schools across the United States at both the collegiate and high school levels are adhering to the Wet-Bulb Globe Temperature (WBGT) to determine the correct way to approach a day’s activities. WBGT is an apparent temperature used to estimate the effect of temperature, humidity, wind speed, and infrared radiation on humans. It is used by athletes, hygienists and the military to determine the appropriate levels of temperature that can be exposed to individuals.

For Coe’s schools, there is a five-step approach to temperature that is followed. Anything under 80 degrees is open for full practice and activity, with water breaks available at regular intervals and when necessary for individuals. Temperatures between 80-85 degrees mandate a water break no less than every 25 minutes. Between 85-87.9 on the WBGT scale demands more frequent breaks for rest and water, and an immersion pool must be on-site. If the number hits 88-88.9 on the WBGT index then all athletes must be under constant supervision, there will be no pads used at practice and water breaks are at five-minute intervals with rest every 15 minutes. Anything 90 degrees or above on the WBGT index, which would be anything over 125 on the heat index, and practice is suspended.

Coe’s coaches all must take the National Federation Of State High School Associations (NFHS) Heat-Illness Prevention course. He said that the course allows coaches to understand why trainers have control over how a practice is run on warm days, and avoid disagreements.

“The education that they receive is important,” Coe said. “After head injuries, heat injuries are the biggest ones…we can’t put a kid’s life in jeopardy.”

Climate Change

At Mashpee (MA) Middle-High School on Cape Cod, Leslie Smith patrols the grounds at one of Massachusetts’ most successful small-school football powers with a Wet-Bulb Globe Thermometer throughout the late summer months as her players work. Smith, who has been the school’s full-time certified athletic trainer for four years, said that she checks the readings at each of the different fields that MMHS has because of the school’s layout.

One of the practice fields, she explained, does not drain well and is protected by woods on three sides. The forest prevents the wind from aiding in evaporation and that particular field can be problematic, especially since it is used primarily for football during the fall. The climate just a few hundred yards away, on the main soccer field, can be very different because of the layout’s openness and better drainage.

“We have to stay on top of things, just to be safe,” she explained.

Smith, who said that she encourages players to drink pickle juice and to suck on mustard packets to help fight dehydration, said she finds that younger players are likely to have more trouble acclimating to the warm weather, but that they also show signs of fatigue earlier. Their lack of experience in the heat leads them to “tend to burn out quicker,” she said.

“We will talk to them early on and tell them that we want them to give 100-percent, but not to ignore the red flag signs that their bodies give them. The younger ones fatigue easier, so we don’t see as much trouble with overheating with them. I find that it’s the older kids that get more (heat) injuries because they might try to go too hard and ignore it and play through. Younger kids are easier to see when they’re starting to struggle, the older kids have been through it before.”

In Mashpee, it is not unusual that the football roster may have just 30 or fewer players on the varsity roster, with a good portion of that made up for first- and second-year players.

Smith added that she also believes that she has to worry just as much about acclimation to cold weather in the late fall.

“The kids are practicing just as much, but they don’t need to take as many breaks because it’s not as hot, but they’re still sweating,” she said. “During night games, when it’s cold, we have to deal with a lot more cramping because the players think that they don’t have to be as vigilant (with staying hydrated) and the cold weather shocks their systems. Their bodies are combating the cool air and their body heat being high because they’re sweating just as much.”