The building blocks to attack man defense

With the 3-point line now firmly entrenched in the game, many teams have shifted to the man-to-man defense to supposedly help reduce the number of perimeter shots against them. Every successful basketball coach must have a fundamentally solid man-to-man offense in his or her arsenal, because a great number of their opponents will play man-to-man defense against their teams.

The following is a summary of concepts and theories of man-to-man offenses that have been developed over many years of studying, coaching, scouting, and observing the game. The concepts that you might incorporate must fit the coaching staff’s personality and philosophy along with its personality, strengths and weaknesses.

Offensive concepts and theories

Many coaches believe offenses should be constructed in a two-phase format, in which there is an instant and smooth transition between both phases. Defenses must then defend both waves of attack and, since there is an instant conversion between both phases of the offense, the defense must also have the difficult task of having the same type of conversion.

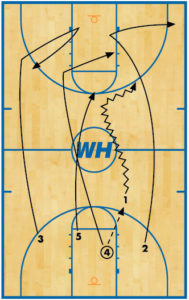

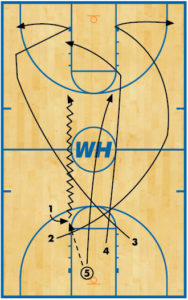

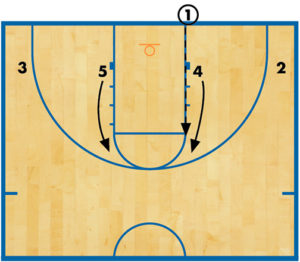

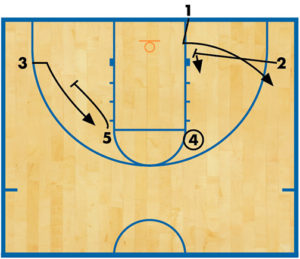

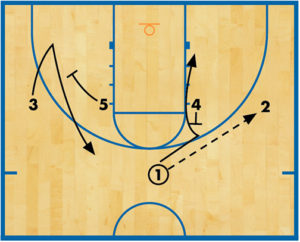

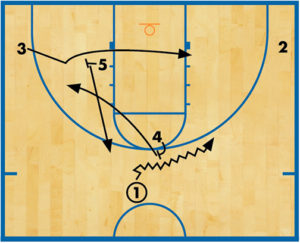

This initial phase could have two separate entities within itself, when dealing with full-court situations. One full-court scenario could be when your team transitions from defense to offense (after turnovers or defensive rebounds) into a primary fast break that does not produce a shot but smoothly converts into the same secondary fast break system. By using a primary fast break, you have more opportunities to beat the opponent’s man-to-man defense in transition by having potential number advantages (DIAGRAMS 1-2).

Another situation could be that a team has to execute some type of a full-court press offense that does not result in a shot, but instead flows immediately into the team’s designated secondary fast break system. A good offensive team must have press offenses that can attack full court man-to-man and zone presses. By using a secondary fast break that flows easily and smoothly from a press offense, the offense has more opportunities to beat the opponent’s man-to-man defense with an organizational advantage over its transitioning from full-court to its half-court defense.

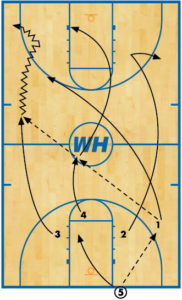

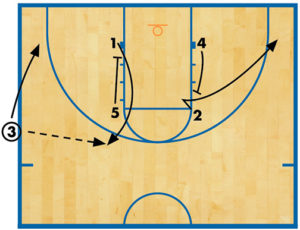

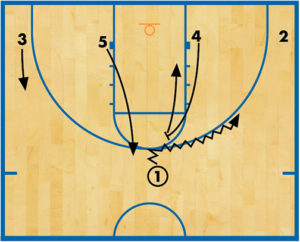

If the secondary fast break fails to produce points, the offensive personnel will almost always end up in “spot-up” positions (DIAGRAMS 3-4).

A team that can mentally handle it should have more than one option in its secondary fast break package. It goes without saying that each option should be able to be executed from both sides of the floor.

Another scenario that could take place in the half-court setting would be when your offensive team must take the ball out of bounds, either from the team’s front-court sideline or from under the team’s basket. Each team should have sideline out-of-bounds plays as well as baseline out-of-bounds plays. Every play from the baseline or sideline must first attack the defense before having a seamless transition into the designated continuity offense.

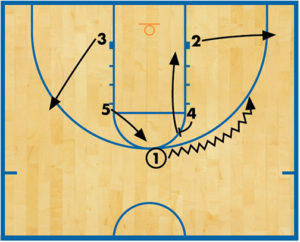

If the sideline or baseline plays, the secondary break or half-court plays do not produce a shot, it positions all five offensive players into specific locations that we define as “spot-ups” (DIAGRAMS 5-7).

Spot-up positions are the designated positions on the floor that allow the offense to have a seamless transition from the initial phase (either after the secondary breaks, out-of-bounds plays and after each entry or play) into the designated continuity offense. The spot-ups of the designated continuity offenses should have the ability to allow all entries and plays, including baseline and sideline out-of-bounds plays and secondary breaks that flow into those continuity offenses.

This puts the pressure on the opposition’s transition defense without giving the defense any time to regroup or reorganize. The continuity offenses that are selected should have the capabilities to smoothly flow from the initial phase into that continuity offense so as to maintain a constant attack on the opposition’s defense (DIAGRAMS 2, 6-7).

The designated continuity offenses are fundamentally sound in concept. They give offensive players structure, but still provide continual fluid movement of both players and the ball. The continuity offenses are the backbone of the overall offensive package, in that teams most likely spend more possession time in the continuity offense than in executing the various plays and fast breaks.

Ruled continuity offenses can consist of basic rules that dictate personnel movement assignments and responsibilities whenever any pass is made, regardless of who passed the ball and who caught it. Continuity offenses should be a balance of inside and outside play, making both phases more effective.

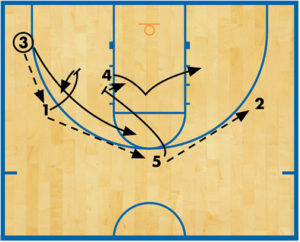

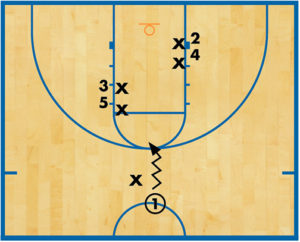

The continuities offenses help provide the offense with high-percentage shots, high-percentage rebounding possibilities, the ability to have a successful defensive transition and a high probability of getting the opposing defense into committing several fouls. The specific rules of each continuity man offense should be similar, but yet not identical. Probably the most frequent scenario is the offensive team bringing the ball into the half-court setting by aligning in a designated half-court alignment and executing a play or entry (DIAGRAM 8).

Entries and alignments

Every style of man-to-man has general types of team weaknesses. Know the particular styles of the man-to-man defense that is being used against you so that you may take advantage on those shortcomings. Using different entries and alignments helps you capitalize on the overall offensive alignments’ strengths; that particular defense’s overall weaknesses; an individual’s offensive strengths; or an opposing individual’s defensive weaknesses.

Different entries can be run out of the various different alignments. The different sets and entries put more pressure on the defense to first defend the alignment, then the entry and then on into the particular ruled man continuity offense employed. Defensive weaknesses can be discovered and taken advantage of, while offensive strengths in the initial set or in the offensive personnel can be maximized (DIAGRAMS 9-10).

Similar entries can be run out of different alignments. The different offensive sets can be implemented to attack a particular defensive man concept or an individual defender. Defenses first must adjust and defend the particular alignment, then the particular entry, and finally the particular ruled man offense continuity employed (DIAGRAMS 11-12).

Different entries can be devised that will “invert” normal perimeter players into converted post players and normal post players could take the role of perimeter players. This method of creating an advantage for the offensive team is called “position mismatches.”

A position mismatch is simply forcing opposing defenders into various situations where they are not skilled, trained or lack the necessary experience to be successful. Position mismatches can provide individual offensive players an opportunity to be in an advantageous position over a particular defense. Hopefully, the techniques learned by individual offensive players through drills provided by the coaching staff enable the them to maintain the position advantage and capitalize on that advantage over the defense.

Designated perimeter players that are taught, trained and drilled in offensive post play techniques could immediately have an advantage over the opposition’s perimeter players. Designated offensive post players that are coached, trained and drilled in offensive perimeter play could also create an immediate advantage for any offensive post player. These position mismatches can be manufactured with specific plays or entries created by the coaching staff, as seen in Diagrams 9-10.

Use a variety of off-the-ball screens in your offense so that you can either completely eliminate or at least move the help-side defense. The screens also allow you to have personnel coming toward the ball either on the perimeter or the interior.

Those types of screens can include the following:

- Lane-exchange cross screens set on the inside

- Diagonal downscreen

- Double diagonal downscreen

- Double or triple stagger screen

- Vertical downscreen (Diagram 7)

- Horizontal perimeter screen

-

Diagram 10 Pin screen (Diagram 6)

- Shuffle-cut screen

- Horizontal or vertical backscreen into the lane with the cutters going toward the basket. Sometimes these are called “flex backscreen” (Diagram 10), and another type is called the “UCLA high post rub-off backscreen” (Diagram 9).

- Brush screen

- Flare screen (Diagram 7)

- Screen the screener (Diagram 10)

Use on-the-ball screens with the screener after the ball screen by doing any of the following:

-

Diagram 11 Rolling to the basket and posting up (Diagrams 11 and 12)

- Stepping out on the perimeter after setting the screen (Pick and pop)

- The screener flaring out on the perimeter after slipping the screen

- Having the original ball screener screen a second teammate (Diagram 10)

- Having the original ball screener receive some form of screen (back-screen and lob or flare screen) to execute some form of screen-the-screener action

Make sure that your defensive transition responsibilities are clear-cut and carried out by everyone. Not only should it be clearly defined as to who “gets back,” but what “getting back” really means — how far back and where.

Also make sure that offensive rebounding responsibility rules are clearly defined and followed through by every offensive player. The three main rebounders should form a triangle around the basket to get rebounds from all angles. Teach rebounders to not get drawn in too far toward the basket.

The right fit

The concepts that a coach might incorporate must not only fit their personality, philosophy and team, but particularly their strengths and weaknesses. The coach must be committed to their beliefs and stand by them in the most difficult times. To stay committed to these beliefs, a coach must carefully choose the concepts that they live by.

These concepts and theories must be utilized to maximize each player’s potential. The volume of the concepts that a coach incorporates has to be relative to their players’ abilities. One year’s squad may vary greatly from the next year’s team. One season’s team may be able to use many different concepts, while next year’s team may have to reduce the number of concepts they use. A good coach must be firmly committed in their beliefs, but also be able to accurately gauge their team’s talent and ability level, as well as their opponents’ talent levels. Choosing which concepts to use for that particular season is a critical decision.

The philosophy of our entire offensive package (full court or half court: man, zone or trap) is to provide our offensive players the maximum number of advantages over the defense. These advantages differ in concept, but all can give an offense even the slightest edge. They can vary from possession to possession and from game to game, and it could be the difference between success and failure.

That edge also may be the difference between a winning or losing season. Capitalizing on any advantages over the defense can and will lead to greater offensive success. Greater offensive success will lead to more team victories, which leads to championships.

John Kimble coached basketball for 20 years in Illinois and Florida, accumulating more than 340 wins. He has authored five coaching books, 90 articles and created 28 coaching videos. He can be found at www.CoachJohnKimble.com.