5 Tips to Freeze Heat-Related Illnesses

Two decades after the tragic training camp death of Minnesota Vikings Pro Bowl offensive lineman Korey Stringer, prevailing attitudes toward heat illness have shifted dramatically.

But even 11 years after the Korey Stringer Institute was formed to provide research, education, and advocacy, heat illness remains an issue where vigilance and preparedness are the best forms of prevention.

“When I first started, water breaks and checking wet-bulb temperatures were non-existent,” says Eric Schwartz, a licensed athletic trainer at Washington Township High School in New Jersey with 20-plus years of experience. “It was macho not to have a water break. More recently, two-a-days were quite prevalent and you would go 4-5 hours, then a short break for lunch, then another 4-5 hours in the middle of August. We just know better now. That’s not appropriate.” Despite the strides made in educating trainers, coaches, athletic directors, administrators, and athletes on the dangers of overheating, 11 football players died in the United States in the past five years from heatstroke, according to the National Center for Catastrophic Sports Injury Research. Seventy have died since 1995.

Despite the strides made in educating trainers, coaches, athletic directors, administrators, and athletes on the dangers of overheating, 11 football players died in the United States in the past five years from heatstroke, according to the National Center for Catastrophic Sports Injury Research. Seventy have died since 1995.

“We know what the research says and many of those situations in the news, it’s preventable when you take the proper precautions,” Schwartz says. “It’s so preventable, and it’s so sad that you see these things happening.”

Here are five steps to ensure you’re doing all you can to prevent heat-related illness.

Have an Action Plan

Developing an Emergency Action Plan, or EAP, is the crucial first step.

“That’s where you start,” says Jim Berry, a licensed athletic trainer at Conway High School in South Carolina. “If you don’t have that in place, everything else is moot.”

Building a plan takes participation and teamwork from administration, athletic directors, coaches, trainers, and local EMS.

“It’s important to plan well before the season starts,” Schwartz says. “You need to work together as a team. It’s a team on the field and it’s a team off the field.”

When developing your action plan, be specific. Cover every conceivable scenario. Ensure your plan includes a chance for trainers and coaches to review any athletes with pre-existing conditions that might predispose them to heat illness.

“Pre-participation physicals to understand any issue ahead of time are really important,” Schwartz says.

Action plans should be reviewed yearly and updated to the most recent best practices.

Obey the Wet Bulb

While having a good weather app is useful, a Wet Bulb Thermometer is a must-have for any athletic program and is now required in some states.

A wet-bulb measures air temperature, humidity, wind, and radiant heat and combines them to create a Wet Bulb Globe Temperature (WBGT). This is not the same as a heat index, and they are not interchangeable.

It’s important to take wet bulb readings at each playing surface, including indoor venues. Your tennis courts might be significantly hotter than your field hockey field. While turf fields are often hotter than grass fields, that’s not always the case. Continue to check throughout the day.

“It’s easy to become complacent,” Berry says. “You think: ‘The wet bulb is green and we don’t have to worry about anything today.’ There are other factors to take into account.”

Once you have your WBGT, there’s an easy color-coded chart to determine which activities are allowed or disallowed. Any reading above 92 means all athletic events should be canceled. During practice, continue to monitor every 15-20 minutes and adjust as necessary.

“Coaches have to be willing to modify,” Berry says.

Be Prepared on Site

Whether it’s a practice or a game, ensuring that proper equipment is accessible quickly can make all the difference.

It starts with hydration systems, from water bottles to water cows. Practices should include at least three water breaks per hour, lasting at least three minutes each. Athletes should be allowed to get water when they request it. The frequency and duration of water breaks should increase as the WGBT rises.

A shady area should be provided close by for student-athletes to use to cool down. If there isn’t a naturally shady area, pop-up tents work.

“You don’t have to spend a lot of money on this,” Schwartz notes.

It is recommended that a cold tub be available near any activity in the heat. These can be Rubbermaid tubs or even a suspended tarp filled with ice water.

“They’re relatively inexpensive,” Berry says. “You can have a few of them and put them at your field location. In the event somebody is having a heat issue, you can cool them rapidly and quickly. That’s the key.”

Keeping an Eagle Eye

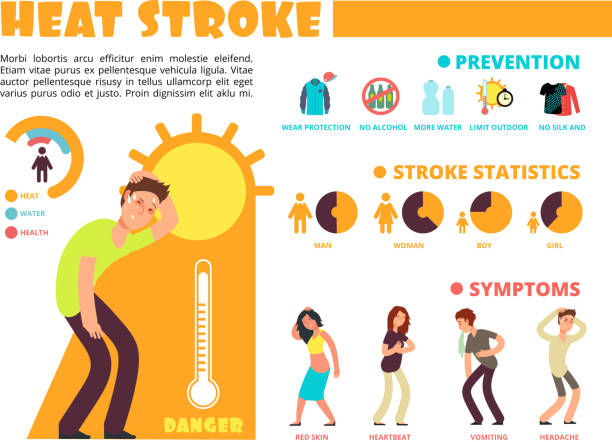

Throughout practice, coaches, athletic trainers, and the student-athletes themselves should be alert for the early signs of heat exhaustion, like lightheadedness, cramping, stumbling, stomach aches, disorientation, confusion, and vomiting.

It’s important to review these symptoms with teams at the start of every season so they can recognize them in themselves or their teammates.

“With our kids, we’ve been preaching this for the last 10 years or so,” Schwartz says. “They’ve been hearing about signs and symptoms since they were in middle school.”

It’s important to keep an eye out for athletes who haven’t eaten properly during the day with Schwartz noting his two cases last year stemmed from not eating lunch.

How To Treat

The first four steps should always happen. Everyone hopes this fifth one never does, but preparation is key. The most important thing to remember is to listen to the athletic trainer or other medical personnel on the scene.

When a student-athlete begins displaying signs of heat illness, they should first be removed to a cooler area, in the shade. Air conditioning is best. Vitals should be taken, including heart rate, blood pressure, and temperature. The extreme zone starts when internal temperatures exceed 102 degrees, Berry and Schwartz agreed.

While emergency services should be alerted immediately, and IVs can help with hydration and blood pressure, it’s important to first cool the overheating athlete before transporting.

“I’m a paramedic myself and it’s amazing how many don’t understand you cool first and transport later,” Schwartz says. “This is not a load-and-go situation, at all.”

Schwartz continued by saying, “I can tell when a kid is going from heat illness to heatstroke. “They will cognitively change. They will be out of it, not know where they are, become combative. You put them in cool water and they’ll become more lucid and start communicating again. … As they become more lucid and more aware of surroundings, that’s a good indicator their body temp has dropped.”

» ALSO SEE: 5 Things You Need to Know About Creatine

Once body temperature has dropped below 102 degrees, it is safe to transport to a hospital.

How to measure that is a dicey topic. The gold standard, according to KSI, is a rectal temperature. But that doesn’t always fly with school administrators, nor parents.

“It is best practice,” Berry says, noting the next-best option is under the tongue. “From the athletic trainer’s perspective, it’s highly recommended. That’s a battle each school district will have to look at. I certainly understand the sensitivity, but you’re talking about a medical professional in a controlled situation.”