Defeating the four-corners delay offense

Most high school and college coaches have observed, studied or used the four-corners delay offense. Therefore, it stands to good reason that a defensive coach likely would have to face this offense in late-period situations or during games when their team is losing.

Defensive teams are traditionally cast as the reactors to the opposition’s offense, but that doesn’t have to be the case. If a defensive team studies the offense, it can generally uncover the offense’s objectives, strengths and weaknesses. Understanding the opposition’s offense can help the defensive team take the initiative and become the “actor,” forcing the offense to react to its approach. When the defense becomes the aggressor with a solid defensive plan of action, it can capitalize on the opposition’s weaknesses and neutralize its strengths.

If a defense knows the offense will not take a certain type of shot, the defensive players can place more pressure on the ball and take more risks. The more restrictive the delay offense, the more freedom defenses have to attack without giving up points.Knowing when, how and whom to substitute can pay huge dividends to the defensive team. It also helps to know the best approach to increase defensive success by fouling.

Even though defensive boxouts after missed free throws are always important, they are even more critical when the opposition is executing a delay game.

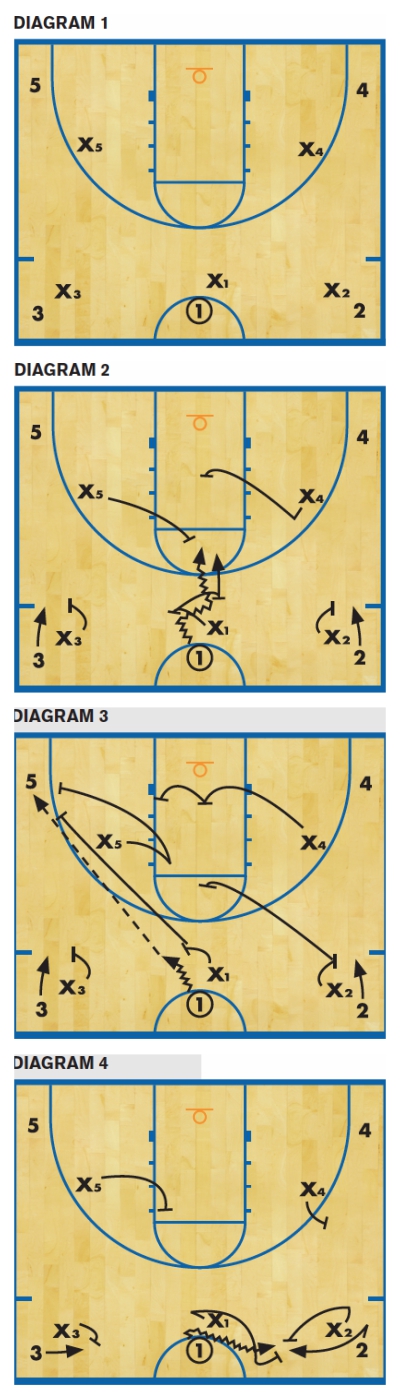

The first diagram illustrates the typical offensive set for the four corners delay game, along with the placement of defensive personnel. The on-ball defender should always be in position to provide maximum efficiency against dribble penetration.

The defensive guard also can be in an overplay stance to:

- Push the ball away from the center of the court, minimizing the floor space that must be defended.

- Force the ball toward the sideline, using it as an extra defender.

- Force the ball-handler to use the weaker hand, deteriorating the overall offense.

- Keep the ball out of the hands of the best player or free-throw shooter.

DIAGRAM 1: X1 forces 1 to their left hand (often the weak hand). In this example, 2 is both a better ball handler and foul shooter than 3, and 4 is a better offensive player than 5. These reasons dictate that X1 force 1 toward their left and away from 2 and 4.

The two defensive wings (X2 and X3) must fight the inclination to sag off their opponents to be in help-and-recover position and stop dribble penetration. Stepping in to help X1 from middle dribble penetration plays into the hands of the four corners offense. The offense wants the dribbler to have safe outlet passes to strong ball-handlers, and to then move the ball back to the center of the floor to restart the offense.

Using a complete denial stance on the two wings forces the ball handler to pass less and dribble more, instead of the normal delay offense. This requires an all-out denial by both wing defenders, regardless of which of the five defenders fill those wing areas.

Coaches must understand that X1 will often require defensive help, but it cannot come from the wings. It must be one of the defensive corners (X5 and X4) who breaks up to attack the dribbler, most likely at the free-throw line or slightly inside the line. This person becomes the “ball player,” while the remaining defensive corner is the “basket player.”

As the ball nears the lane and the ball player attacks the dribbler, the basket player breaks to the center of the lane to form a defensive tandem. The first corner defender stops the ball, while the second corner defender protects the basket. The original ball defender remains aggressive on the dribbler and continues to hound the ball from behind or on one side of the dribbler.

During the dribble penetration, X2 and X3 continue to deny their men any form of a kick-out pass. DIAGRAM 2 shows X2 and X3 executing successful pass denial defense with X1 forcing 1 to dribble-penetrate with the weak hand. The designated basket player could be the defender on the weaker corner player (5). X1 remains on 1 and almost forms a double-team on the ball. Without safe wing passes, the defense could produce a turnover.

When the new ball player (X5) and the original defensive guard (X1) stop penetration, they discourage layups and pull-up jumpers.

Sometimes, the defensive team is forced to step up the pressure by double-teaming particular ball handlers in specific areas of the court. Successful traps must:

- Take place near the sidelines, baselines or timelines, using them as extra defenders.

- Pressure the ball-handler without committing cheap fouls.

- Designate one defender who protects the basket and two defenders as potential interceptors.

- Rotate defenders to the anticipated new location of the ball, and avoid watching the escape pass or dribble.

If the ball is passed into the deep corner, that might be an ideal time for the defensive team to trap the ball, because:

- The sideline and baseline restrict ball movement.

- The ball is on one side of the floor, clearly defining a defensive ball side and help side.

- The ball is most likely in the hands of a poor or inexperienced ball-handler, passer or free-throw shooter (DIAGRAM 3).

If 1 makes a shallow dribble towards 3 (or 2), and 3 cuts behind the ball on the side of the timeline, it could give X3 a “free trap” of the ball because of their proximity to the ball and the distance between their original man and the basket.

If 3 or 2 set ball screens for 1, or there is a two- or three-man weave action, traps are encouraged because of the same low defensive risks and high rewards for the defense (DIAGRAM 4).

This approach can turn the time-score deficit into a positive situation for defenses. By creating a detailed plan of attack, coaches can spoil the opponent’s delay game and swing momentum in their direction. That places the pressure back onto the shoulders of their opponents.

John Kimble coached basketball for 23 years in Illinois and Florida at the college and high school levels, accumulating more than 340 victories. He has authored five coaching books.