Shoulder development in strength training

The muscles that make up the shoulder region require special attention in a strength training program. After all, many sports depend upon extensive use of the hands and arms in throwing, catching, swinging and combative or collision skills (e.g., football and wresting), thus forcing athletes to rely heavily on their shoulders for strength and power production.

The actual shoulder complex is comprised of a large aggregate of interwoven, superficial and extrinsic musculature and connective tissues that create movement of the scapula, clavicle and humerus.

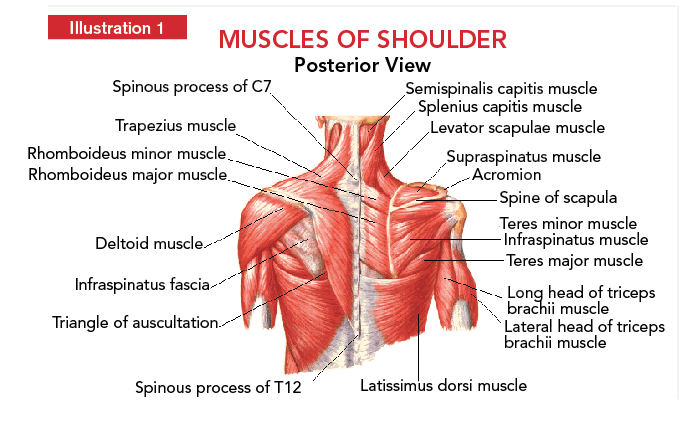

Illustration No. 1 depicts much of the vital posterior (rear) musculature, with the superficial muscles shown on the left, and some of the intrinsic structures on the right.

A short list of the primary superficial and intrinsic muscles illustrated that assist with arm movement and act as a ballast for the region are:

- Deltoids (3 heads: anterior, medial, posterior) abduct, flex, extend and rotate the arm.

- Latissimus Dorsi adducts, medially rotates and extends the arm.

- Trapezius elevates, depresses, rotates and flexes the scapula; also extends the neck.

- Rhomboids: (minor and major) retract, rotate and fix scapula.

- Teres Major adducts, extends and medially rotates the arm.

The following rotator cuff muscles form a cap over the proximal end (top) of the humerus: Infraspinatus (extends and laterally rotates the arm); Subscapularis (extends and medially rotates the arm); Supraspinatus (abducts the arm); and Teres Minor (adducts and laterally rotates the arm).

The shoulders highly involved job description and liberal dexterity make it one of our most useful, functional joints. However, its freedom of movement and interdependence with so many different sports skills can prove to be a double-edged sword, as overuse and injury are common dilemmas.

We do our very best to place special emphasis on this area, and we would like to use this installment of POWERLINE to share just a handful or so of our favorite movements. It is not an end-all list, but it is a good start, and we will offer more suggestions on training this vital area in future columns.

Magnificent seven for the shoulder

In no particular order, let’s take a look at seven movements we incorporate at various junctures in our upper-body training regimens. First off, we will discuss the exercise technique for each, and then offer some suggestions and coaching points for implementation.

1. Log Bar Incline: The incline press has always been one of our favorite multi-joint movements for the anterior shoulder, as well as for the pectoralis (chest) and triceps (posterior arm) muscles. The incline position (as opposed to the supine position) often serves to mitigate a litany of shoulder anomalies and the pain that often accompanies them.

The log-bar handles place the hands in a tighter, neutral grip position, which can also abate certain shoulder impingement issues.

With the assistance of a good spotter, the lifter positions the bar over the top of his or her shoulder region, and then lowers it (eccentric phase) with control to a target area between the mid-line of the chest and the clavicles (collar bones). A light touch to that area is followed with a forceful, yet controlled, press (concentric phase) back to the original position. There should be a slight arcing path from the mid-range/chest position to the top of the press.

Coaching Points: In our program, this is a primary, multi-joint upper body movement, and it is usually performed once per week. Work sets (i.e., those that are recorded and tracked) vary depending upon other exercises being implemented within the same script, but are usually in the range of three to four.

Repetitions also vary, but the norm is somewhere in the six to 10 range. (Note: For more information on obtaining the log bar, go to www.functionalhandstrength.com.)

2. Front Arm Raise/Flexion: The front arm raise targets the anterior deltoid head when correctly performed. The lifter uses either a neutral (thumbs-up) grip as pictured, or a pronated (palms-down) grip, and then raises the straight arms to a slightly higher-than-parallel position to the floor.

After a momentary pause, the arms are lowered to the starting position in about 3 to 4 seconds. As soon as the starting point is reached, the next rep is executed with no respite.

The lifter is either required to use a weight than requires an all-out effort for eight to 10 perfectly performed reps, or is instructed to execute reps for time under load (TUL), which can range anywhere between 30 to 60 seconds. Two to three sets are normally executed.

3. Lateral Arm Raise/Abduction: This movement primarily targets the medial deltoid head.

Starting with the arms held straight against the outside of the body, the lifter raises the arms with a palms-down position to a point slightly higher than parallel to the floor.

After a slight pause in that position, the arms are lowered to the start in about three to four seconds. Again, when the starting point is reached, the next rep is immediately executed.

As with the front arm raises, we utilize either two to three sets of eight to 10 reps or some form of a TUL protocol in a given script.

4. Upright Row: We use this as a combination exercise to recruit involvement from both the trapezius and the more localized shoulder compartment. From a straight-arm position with a relatively narrow grip (as pictured with the use of a 100-pound sandbag), pull the arms upward as high as possible with the elbows flared outward. Pause briefly to demonstrate control, and then return to the start in about 3 to 4 seconds. The same systems for sets or reps used on the front and lateral raises are in effect here as well.

Coaching Point: You may encounter some individuals who suffer from any one of a variety of gleno-humeral impingements (e.g., osteophyte formation within the joint space), which contraindicate this movement. If pain is present at any point when performing this exercise, it should be discontinued. A straight-arm shoulder shrug (i.e., elevating the shoulders upward to the ears, pausing briefly and then returning to the start) can be substituted.

5. Face Pull: Using a 1-inch flex band that is attached to the power racks, the lifter assumes an overhand grip (thumbs-down) and pulls the band to nose level. A slight pause is incorporated at this point, and then the band is returned to the start in three to four seconds. It is important to slide the band up or down the rack post to achieve a parallel position with the band when it is in the mid-range position, as pictured.

Coaching Point: This exercise along with the external and internal rotations that follow is a great between-set adjunct. We use them between sets of supine, incline and military presses to be assured that we are addressing some of the intrinsic and posterior structures to help balance the work we are doing for the large superficial muscles with the aforementioned big lifts.

6. External Rotations: With the arm positioned at 90 degrees and the elbow held tight to the side of the body, a 1/2-inch flex band (also attached to the power racks) is pulled in an external/lateral direction.

The lifter is instructed to pull the band externally as far as possible without the elbow losing contact with the side of the body.

After a slight pause, the band is returned to the starting position in three to four seconds. Keep the band attached in a direct line with the hand as it is held in the 90-degree position.

7. Internal Rotations: The lifter needs only to turn to the opposite direction of the external-rotation exercise, start with the arm in a 90-degree, externally rotated position and then internally/medially rotate the arm to the mid-line of the body.

Coaching Point: A great way to incorporate external and internal rotations is to alternate them between the sets of various pressing movements.

Final rep

While not all-inclusive, this compilation of shoulder movements addresses much of the extrinsic and intrinsic shoulder musculature in a fashion that is easily learned and readily adaptable for male and female athletes.