Dr. Jack Ramsay: My 60 years in basketball

Throughout the year, Coach & Athletic Director will go back 25 years to share some of our best articles from 1994. The publication, formerly Scholastic Coach magazine, is in its 89th year of production. What better way to celebrate our longevity than to show what we’ve done and where we’ve been.

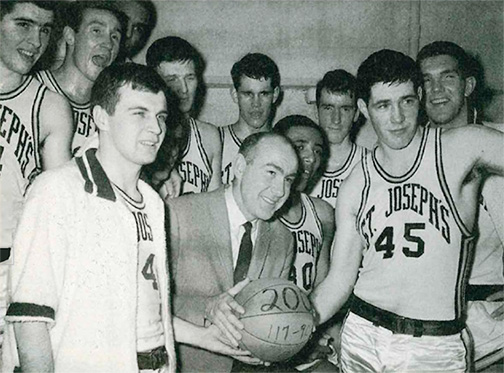

This article, written by Hall of Fame basketball coach Dr. Jack Ramsay, was published in our October 1994 edition.

It was totally unsupervised — wild, error-filled forays up and down the court, the player with the ball dribbling at top speed toward his basket, his eyes riveted on the ball. Teammates ran after him, shrieking his name, begging him to pass the ball. The only time the dribbler gave up the ball was when defenders knocked it loose or cut off all possible avenues to the hoop.

I learned that a major part of coaching was teaching, not just showing and telling.

The process was then repeated by the next player with ball possession until someone took a shot. Occasionally, a goal was scored. After everyone had had a chance with the ball, the process was repeated. Basketball it was not, but we had fun and kept at it until totally exhausted.

As crude as those efforts were, I felt a great fascination for this game. My dad attached a hoop to the barn behind our house and I spent hours out there, year round, learning to dribble and shoot. My backyard soon became a kind of center for other kids who liked basketball.

We played half-court games, and like most kids in rural lots or urban playgrounds all over the United States, we accidentally learned to pass, screen, rebound and defend, as well as dribble and shoot. That experience helped prepare thousands of kids like myself for organized basketball at the school level.

Learning the game

My family moved to the Philadelphia area when I was in 10th grade. I enrolled in a larger school and faced a much stronger level of basketball competition. The reigning power in Pennsylvania at the time was Lower Merion High School, a conference rival of my school, Upper Darby. In my three years of basketball, Lower Merion won the State Championship each year.

The experience taught me what kind of impact a coach can have on his team. Lower Merion’s coach, Bill Anderson, played the same game every year, executing crisp passes, quick give-and-go cuts, flash post-ups, and tough man-to-man defense. No frills or gimmicks. Just good, solid, fundamental basketball. Years later, I heard that style referred to as “eastern” basketball.

Other area teams tried to emulate Lower Merion, but never came close, It was clearly the coach who was responsible for the team’s exceptional success. His players were sound and well-schooled fundamentally — good enough to make All-State, but rarely all-anything as college players. Coach Anderson made an indelible impression on me.

My coach at St. Joseph’s College was Bill Ferguson, who was also a math teacher and part-time banker. Fergie was not much of an X and 0 exponent. He allowed his teams to create their own play action, but he did insist on hard, aggressive effort.

In those years (early 1940s), St. Joe’s hosted double-headers along with La Salle and Temple in Philadelphia’s Convention Hall. They were part of a regional program organized by Ned Irish for Madison Square Garden. Irish scheduled the best college teams in the country to play first in Buffalo (against Canisius, Niagara or St. Bonaventure), then to meet our group in Philadelphia, and finish in New York (facing St. John’s, CCNY, Manhattan, NYU, or LIU).

» RELATED: Dr. Jack Ramsay: 12 ‘absolutes’ in coaching

The program provided great intersectional competition. UCLA, Southern Cal, Oklahoma A&M, Texas, Kansas, Kansas State, Kentucky, Western Kentucky, Tennessee, Duke, North Carolina, North Carolina State, Rhode Island State, and other perennially strong teams appeared regularly at the three sites. The host colleges also played each other.

During my four years at St. Joseph’s, interrupted by three years of Navy duty during World War II, I played against some of the best teams, players and coaches of that time. It was fascinating to see the different styles that some of the giants of the coaching profession brought to Philadelphia.

Coach Frank Keaney’s Rhode Islanders were the first to race up and down the floor with what he called “Firehouse” basketball. In contrast, Coach Hank Iba’s Oklahoma A&M teams played a physical, bruising defensive game; then stressed a ball-control offense.

Eddie Diddle combined the two styles at Western Kentucky, with an array of tall, talented, agile players; and CCNY’s Nat Holman had a slick, quick game that won both the NIT and NCAA championships in the same year (1950) — the only grand slam in history.

My Navy duty gave me the chance to play briefly with the San Diego Dons while awaiting re-assignment on the west coast. The Dons were a strong AAU team that featured the great Jim Pollard. It employed a “western” style, using weak-side screens and ball reversals rather than the give-and go “eastern” style I had grown up with.

My Navy duty gave me the chance to play briefly with the San Diego Dons while awaiting re-assignment on the west coast. The Dons were a strong AAU team that featured the great Jim Pollard. It employed a “western” style, using weak-side screens and ball reversals rather than the give-and go “eastern” style I had grown up with.

I was lost in the system, and was transferred before I had time to really adjust to it. But I learned again, this time from first-hand experience, that there were other ways to play the game effectively. I also left the Dons with a deep appreciation of Pollard’s tremendous skills. He was the Michael Jordan of his era.

Catching the coaching bug

Before my playing days ended, I also managed to play against Bob Kurland, Dick McGuire, Slater Martin, Paul Arizin, Joe Fulks, and Neil Johnston — like Pollard, future Hall of Famers who had an impact on how the game was played. I learned something from each of them.

I came out of those years with a strong desire to coach. There was something intriguing about taking a group of players, teaching them to play your game, and finding a way to win with it.

I wanted the opportunity to help increase the player’s skills; to get them to play selflessly as a unit; to demand that they go at it with intensity and poise; and to play only to win in the same way those great coaches appeared to have done.

The game is always being played in greater numbers and with constantly improving skills — everywhere.

By combining high school teaching-coaching jobs with playing in the Eastern Professional League for the next six years, I was able to continue my awareness of the game from a player’s perspective while teaching the game and developing an effective system of play.

Two of my teammates in the Eastern League were Jack McCloskey and Stan Novak, also high school coaches in the Philadelphia area who went on to have distinguished NBA careers. We traveled together by car to weekend pro games and, during the long rides, we shared ideas about how to coach the game and discussed strategies that had or had not worked for our high school teams. The trips became a kind of coaching clinic on wheels.

I needed all the help I could get. My adjustment to coaching was more difficult than I had expected. I had thought because I played against great teams, players and coaches, I could easily transfer those experiences to my players. It wasn’t that simple.

I learned that a major part of coaching was teaching, not just showing and telling. I found that, although all coaches had a system of play, the good ones often adapted it to fit the special skills of their players. Well-coached teams were never surprised. They seemed prepared for anything that happened in a game. They could make an effective adjustment for any quickly changing situation.

I watched opposing coaches do a better job of motivating their players and teams. And I wanted my players to exhibit more poise under pressure, but understood that I could not expect it from them until I could demonstrate it myself. I needed to become a better coach.

» ALSO SEE: John Wooden shares his fast-break offense

After my St. James (Chester, Pennsylvania) H.S. team struggled through a couple of seasons in the tough Philadelphia Catholic League, I increased my intensity to improve. I saw as many games as I could — high school, college and professional — live and on television. And I carefully observed coaches and noted their attention to detail and their inner team relationships.

I sent to the NCAA office for game films of the tournament finalists and pored over them, I attended coaching clinics to hear the great coaches speak about their techniques.

Defense, these coaches said, was the key to winning. And it didn’t have to be the conventional man-to-man. At that time, teams were having success with various zone defenses — matchups, traps, and combinations, like box-and-one. These were different tactics from those I had experienced as a player, and so I gave them full attention — ultimately incorporating some of them into my system.

The first zone trap I ever saw was used by Coach Woody Ludwig at Pennsylvania Military College (now Widener College) in 1949. Legendary coach John Wooden achieved enormous success with it during his incredible run at UCLA and it helped my teams win a ton of games at St. Joseph’s College and in the NBA.

The matchup zone defense, popular among Philadelphia area high school coaches, reached its peak of effectiveness with Harry Litwak’s great Temple teams of the late ’50s. Then Frank McGuire won an NCAA title with North Carolina in 1957 with a standard 2-1-2 zone defense.

Aggressive, jump-switching man-to-man defense — which I first saw used successfully at the college level by Pete Newell at California (1959 NCAA champions) and by Eddie Donovan at St. Bonaventure — wrought havoc with the opponents’ carefully executed plays.

Dean Smith did the same thing at North Carolina, and added an in-and-out, shuttling system of substitutions.

Red Auerbach’s Boston Celtics brought pressure defense into the NBA, and combined it with the shot-blocking and intimidation threat of Bill Russell to win eight consecutive titles (1959-66).

Russell was the first player to make the blocked shot an offensive as well as defensive weapon. He blocked the shots and his teammates ran for fast breaks with the possessions. Big Bill was also the mainstay of Coach Phil Woolpert’s San Francisco team that won back-to-back NCAA titles in 1955 and ’56.

I believe Bill Russell had a greater impact on the game than any other player in history. Offensive styles also changed during my period of observation. In the late 1940s and early ’50s, the half-court series run by Adolph Rupp at Kentucky was totally different from the five-man weave of Ken Loeffler at La Salle — but both won NCAA championships.

Ed Juecker showed it wasn’t necessary to fast break to win, when he took his Cincinnati team to consecutive NCAA championships in 1961 and ’62 with a ball-control game similar to that of Newell’s at California.

Bob Knight used a passing, screening game — somewhat related to the old, “eastern” style — to win three NCAA titles for Indiana; while Mike Krzyzewski’s Duke teams won back-to-backs with a combination passing game and pro-type screening offense. Both schools played rock-ribbed, man-to-man D.

In the NBA, the Celtics used the same six half-court plays during their reign of terror, on those occasions when they weren’t fast breaking. The plays were fundamentally sound, yielding shots well-suited to the abilities of their players.

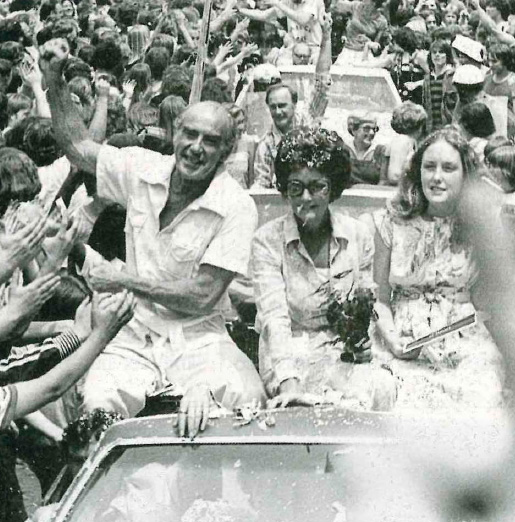

My championship Portland team ( 1977) used the consummate passing skills of Bill Walton to feed cutters at the basket. Magic Johnson was the master floor general of Pat Riley’s fast-breaking Lakers that dominated the 1980s; although Boston bounded back to win two championships sparked by the all-around wizardry of Larry Bird.

Then Detroit won back-to-back titles with a productive, three-guard attack orchestrated by Chuck Daly; and later Chicago won its celebrated “Three-peat” with Jordan, the game’s greatest player, at center stage.

Bulls coach Phil Jackson didn’t just give Michael the ball and clear the floor, Chicago used an offense that assistant Tex Winter developed at college. It designated spot positions on the floor and required specific screen, pass and cut continuities. The positions were interchangeable to accommodate Jordan’s considerable skills, and the offense was flexible enough to afford M.J. some one-on-one bursts to the hoop.

Those varying, sometimes conflicting, styles of offense and defense proved once again that theory, however sound, is less important than execution in determining success … And that attention to detail is the key to good execution.

Since ending an active coaching career, I have stayed close to the game, mostly as a television analyst, but also giving coaching clinics around the world for the NBA.

The level of international basketball has greatly improved, and so have its players. The number of great NBA players whose roots are in foreign soil attest to that: Olajuwon, Ewing, Schrempf, Petrovic, Kukoc, Divac, Mutombo, Marciulionis, Herrera, Smits, and Seikaly have made their marks in the NBA — and more will come.

The game is always being played in greater numbers and with constantly improving skills — everywhere. But no matter where or when I have seen the game played, it has always had constants — indigenous, never-changing concepts. I have thoroughly enjoyed playing this great game and have always felt honored to be known as one of its coaches.